Tech and Stability – Two years ago, a massive global pandemic known as the covid-19 changed the world as we once knew it. The pandemic changed the world in ways few could have predicted: from healthcare infrastructure to agricultural practices to entertainment—everyone from scientists to children were affected. But for a small group of engineers and programmers who work in virtual reality, this crisis has been a boon.

Once the domain of professional video game designers and tech-savvy early adopters, virtual reality is now a ubiquitous part of daily life. VR headsets are everywhere: in schools, at work, at home. Families watch movies together in virtual environments; friends enjoy music together; children play games with each other in simulated worlds. It wasn’t just the loss of human life that changed the world, it was the devastating psychological trauma caused by separation from loved ones—people who now live on opposite sides of an endless quarantine zone. Now, millions of people connect to each other through VR for entertainment and support.

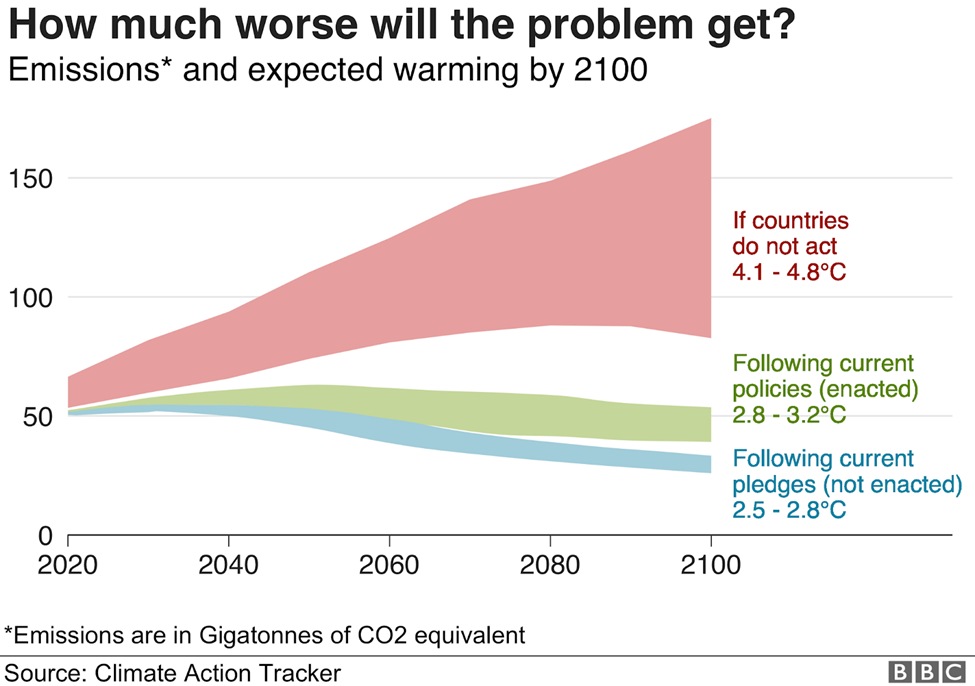

The development of shared immersive technology could be the answer to greener gaming. Virtual reality (VR) is often heralded as the future of gaming, but it’s not without its problems.

The cost of VR is notoriously high, and the headsets themselves are demanding – they need to remain plugged into a PC for power even when you’re not using them, which means they can be an environmental nightmare if they’re left on for months at a time. But it turns out that “shared immersive technology” like the HTC Vive might be able to fix this problem altogether.

“Shared immersive technology” is a catch-all term for technologies that allow you to have a shared experience with other people, whether it be in the form of a 3D space or a virtual one. The “shared” part means that the experience does not have to be limited to one person at a time but instead can be shared by multiple people. The “immersive” part means that it can simulate a real-life experience. This technology would be a leap forward from the current VR systems, which allow only one person to have an exclusive VR experience at a time.

Companies like Hulu and Netease are already implementing shared immersive technology, but these aren’t truly shared experiences. Rather, they only allow a different person in the same room to control what’s happening on a different computer. But these systems require an expensive set-up with the right hardware to run them properly – making them more affordable for home use would sell millions of new users on VR’s potential, not just through video games but through social interactions as well.

This is where HTC’s Vive comes in. Rather than being a standalone device, the Vive is basically a computer running SteamVR software that allows you to use multiple headsets together with the use of IoT devices. Four can be arranged side by side on two sets of bases, making the set-up feel more like you’re in one big room instead of four separate ones. If you’ve ever played any action game with higher than medium settings, then you know that the computer struggles to keep your field-of-view steady without stuttering and other minor issues. The Vive, however, is able to keep a frame rate that felt acceptable to me, even with a framerate counter running at the bottom right of my vision.

To test out the Vive’s capabilities as a shared immersive technology device, HTC set up a demo called River Tubing. The player laying down on his stomach has a first-person view of a riverbed below him, while the four people standing by his side each have their own third-person perspective of him lying there. They use their hands to move objects around him and humorously throw them into the water. Even a few hundred feet away from the walls of a room, holding up my head to look around felt natural and immersive.

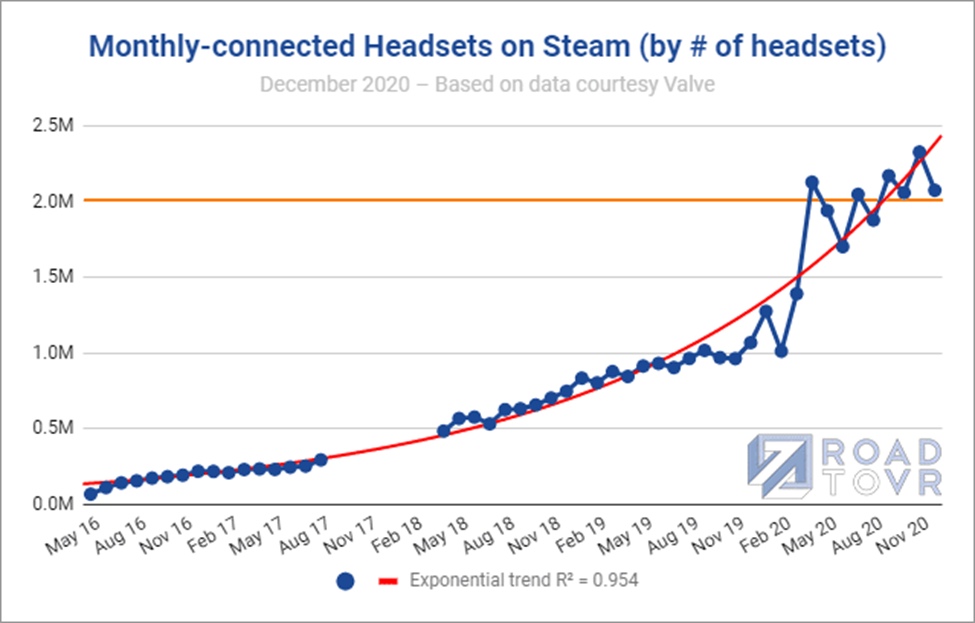

However, the real test of shared immersive technology was walking through a 3D world that others could see. The River Tubing demo was a success, but VR isn’t going to be a shared experience if the headsets themselves are too expensive. That’s why Vive needs to sell millions of units at a low price to make VR a mainstream product that everyone can afford. An essential step in that direction is offering a computer that runs SteamVR at under $500. Assuming Vive wants to create an entire ecosystem around SteamVR and Steam, this would be enough to boost sales, so HTC can afford to offer reasonable prices for hardware and develop experiences people will want.

Vive’s strength is in its ability to act as the centre of a shared experience, which is why SteamVR will likely be the centre of Vive’s offering. So if you want to make the most out of your hardware, then sharing it with others means that you’re not just wasting power on empty spaces. It also means that your headset will be used for many hours at a time if everyone is taking turns wearing it. This makes it an investment that pays off much more than just having fun playing games – it could save gamers money and help the environment at the same time.

Here’s one example: imagine having to take your PC offline after “only” using it for 16 hours. That might only cost a few cents, but it adds up. Over a year, a gamer can spend thousands in electricity costs for a PC that’s mostly idle. But in the case of the Vive or any other shared immersive technology system, that same headset could be used for hours every day without consuming extra power from the wall.

It’s hard to know how long it will take for this sort of technology to become mainstream. Of course, a great deal depends on Valve and HTC’s success with the Vive. But given how close we have come to getting VR right with the original HTC Vive demo, there is no doubt that we will see more devices like it in the near future.